Bitzer Was a Banker! – Reasons to Learn Hebrew and Greek

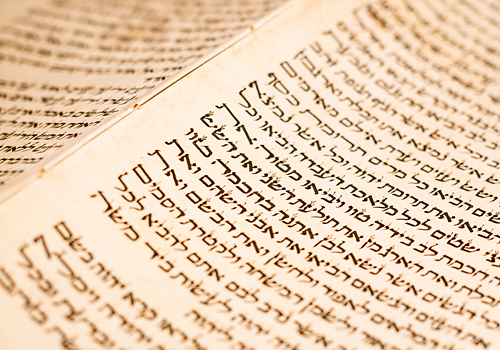

I've been very inspired by the article "Bitzer Was a Banker!" by John Piper. It's about reasons for learning the original languages of the Bible. I first saw the article quoted in the first Hebrew textbook I bought, when I was looking through it in the bookshop — and it helped convince me that I wanted to learn Hebrew and Greek.

John Piper writes about Heinrich Bitzer — a banker (not a pastor or theologian) — who learned the original languages of the Bible and promoted their use. My textbook ("Basics of Biblical Hebrew" by Gary D. Pratico and Miles V. Van Pelt, 2nd Edition) cites the article from John Piper's book, "Brothers, We are Not Professionals: A Plea to Pastors for Radical Ministry", Broadman & Holman, 2002. I've added the bolding and other emphasis to the quotes myself.

You can read the full text of the article "Bitzer Was a Banker!" here as a PDF.

I'll give a few quotes from it below:

Most seminaries, evangelical as well as liberal, have communicated by their curriculum emphases that learning Greek and Hebrew may have some value for a few rare folks but is optional for the pastoral ministry. I have a debt to pay to Heinrich Bitzer, and I would like to discharge it by exhorting all of us to ponder his thesis:

“The more a theologian detaches himself from the basic Hebrew and Greek text of Holy Scripture, the more he detaches himself from the source of real theology! And real theology is the foundation of a fruitful and blessed ministry.”

Several things happen as the original languages fall into disuse among pastors. First, the confidence of pastors to determine the precise meaning of Biblical texts diminishes. And with the confidence to interpret rigorously goes the confidence to preach powerfully. It is difficult to preach week in and week out over the whole range of God’s revelation with depth and power if you are plagued with uncertainty when you venture beyond basic gospel generalities.

Weakness in Greek and Hebrew also gives rise to exegetical imprecision and carelessness. And exegetical imprecision is the mother of liberal theology.

Further, when we fail to stress the use of Greek and Hebrew as valuable in the pastoral office, we create an eldership of professional academicians. We surrender to the seminaries and universities essential dimensions of our responsibility as elders and overseers of the churches. I am deeply grateful for seminaries and for Bible-believing, God-centered, Christ-exalting scholars. But did God really intend that the people who interpret the Bible most carefully be one step removed from the weekly ministry of the Word in the church?

Acts 20:27 charges us with the proclamation of “the whole counsel of God.” But we look more and more to the professional academicians for books which fit the jagged pieces of revelation into a unified whole. Acts 20:28 charges us to take heed for the flock and guard it from wolves who rise up in the church and speak perverse things. But we look more and more to the linguistic and historical specialists to fight our battles for us in books and articles. We have, by and large, lost the Biblical vision of a pastor as one who is mighty in the Scriptures, apt to teach, competent to confute opponents, and able to penetrate to the unity of the whole counsel of God. Is it healthy or biblical for the church to cultivate an eldership of pastors (weak in the Word) and an eldership of professors (strong in the Word)?

... Yet what is more important and more deeply practical for the pastoral office than advancing in Greek and Hebrew exegesis by which we mine God’s treasures?

Why then do hundreds of young and middle-aged pastors devote years of effort to everything but the languages when pursuing continuing education? And why do seminaries not offer incentives and degrees to help pastors maintain the most important pastoral skill — exegesis of the original meaning of Scripture?

No matter what we say about the inerrancy of the Bible, our actions reveal our true convictions about its centrality and power.

I remember reading the quote below by George Whitefield while sitting on the carpet floor of the bookshop, flicking through the textbook, and thinking about whether or not to buy it. And whether or not to seriously start making plans to learn these languages. I've got some ongoing physical health issues that have prevented me from doing many things. Reading this quote greatly inspired me, and gave me the idea (and a feeling of confidence) that learning the original languages of the Bible might be something I could really do, even with less than perfect health:

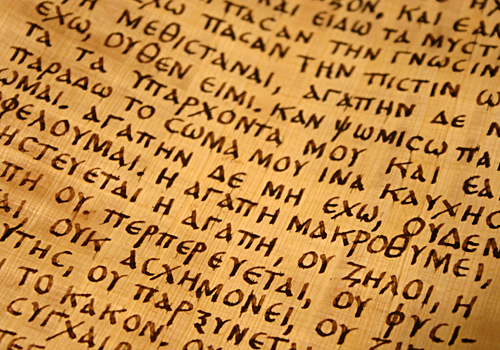

In the Methodist Archives of Manchester you can see the two-volume Greek Testament of the evangelist George Whitefield liberally furnished with notes on the interleaved paper. He wrote of his time at Oxford,

“Though weak, I often spent two hours in my evening retirements and prayed over my Greek Testament, and Bishop Hall’s most excellent Contemplations, every hour that my health would permit.”

Martin Luther thought the original languages of the Bible were essential to his whole mission:

Luther said, “If the languages had not made me positive as to the true meaning of the word, I might have still remained a chained monk, engaged in quietly preaching Romish errors in the obscurity of a cloister; the pope, the sophists, and their anti-Christian empire would have remained unshaken.”

In other words, he attributes the breakthrough of the Reformation to the penetrating power of the original languages.

Luther spoke against the backdrop of a thousand years of church darkness without the Word when he said boldly, “It is certain that unless the languages remain, the Gospel must finally perish.”

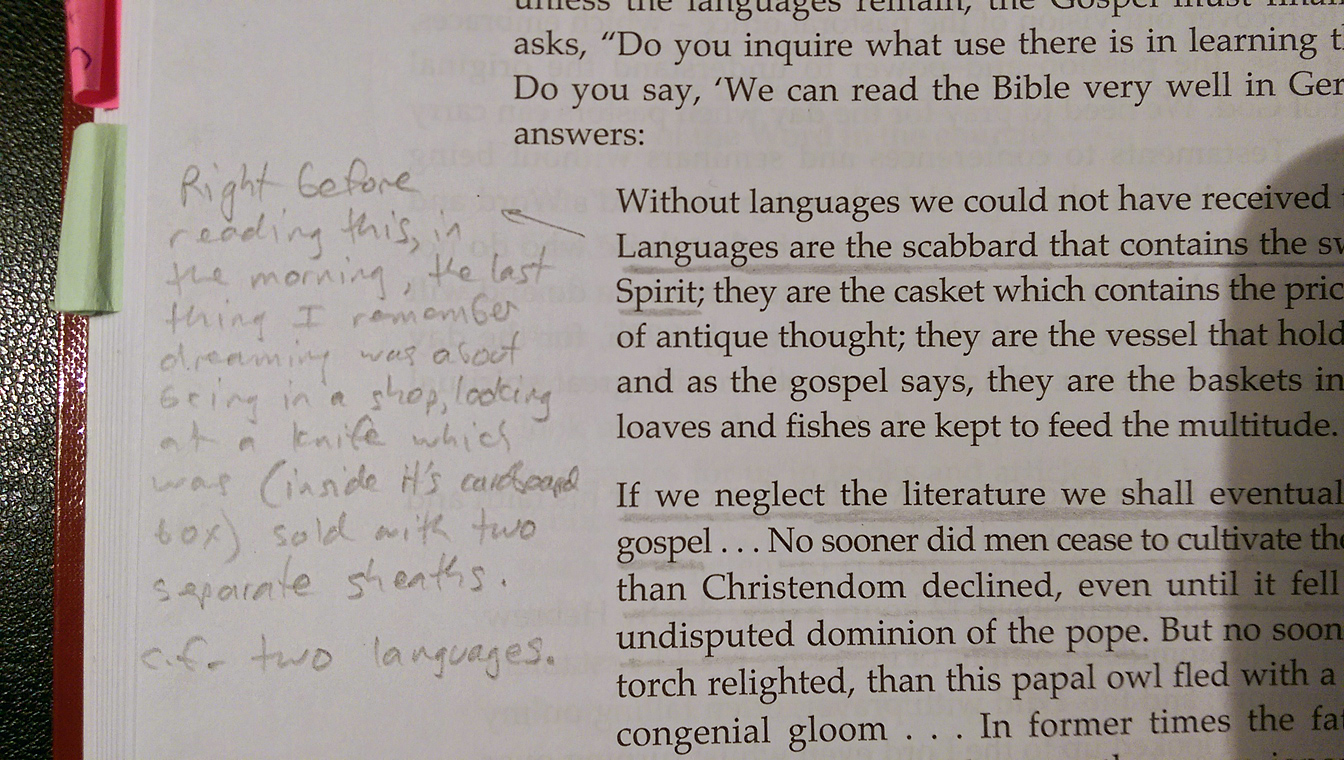

I was flicking through my Hebrew textbook (containing this quoted article about Bitzer) one morning immediately after waking up from a dream. In my dream, I was in a shop looking at a fancy survival knife, which was sold in a box containing two different, separate sheaths. After waking from that dream, I randomly opened my textbook and my eyes went straight to this:

Without languages we could not have received the Gospel. Languages are the scabbard that contains the sword of the Spirit; they are the casket which contains the priceless jewels of antique thought; they are the vessel that holds the wine; and as the gospel says, they are the baskets in which the loaves and fishes are kept to feed the multitude.

If we neglect the literature we shall eventually lose the gospel. . . No sooner did men cease to cultivate the languages than Christendom declined...

Before reading this section of “Bitzer Was a Banker!”, I'd just woke up from a dream about a survival knife which was sold with two separate sheaths in the box — and I was wondering to myself what each of them would be for, and why there would be two of them.

I then wrote the above note on the page in pencil. Which I later forgot about, and found again when I came back much later to re-read the article.

The relevance of the fancy survival knife in my dream is that for some of my life, beginning as a young child, and inspired by my father, I used to think a lot about the idea of learning to survive in the bush with just a knife and nothing else. I always liked the idea of just having one main, special, sacred object that's all you really need to live your life with. Due to physical health problems I was never able to get very far with that goal of wilderness survival with just one knife. In more recent years, that one main, special, sacred object that's all I really need to live my life with has become the Holy Bible.

Here's a few more quotes:

Brothers, perhaps the vision can grow with your help. It is never too late to learn the languages. There are men who began after retirement! It is not a question of time but of values.

The original Scriptures well deserve your pains,and will richly repay them.

Continuing education is being pursued everywhere. Let’s give heed to the word of Martin Luther: “As dear as the gospel is to us all, let us as hard contend with its language.” Bitzer did. And Bitzer was a Banker!!

Click here to read the full text of the article "Bitzer Was a Banker!" here as a PDF.